History&Geography

History

Sambians (before 1255)

The territory of modern Kaliningrad was inhabited by Sambians or ancient Russians, known as Tvangste (the Prussian word tvinksta means a pond formed by a dam), as well as several ancient Prussian settlements, including the fishing village and the port of Lipnik (now it and the territory of Sakkame are part of the Leningrad region of Kaliningrad), as well as farming the villages of Sakkame and Trakkame.

The arrival of the Teutonic Order

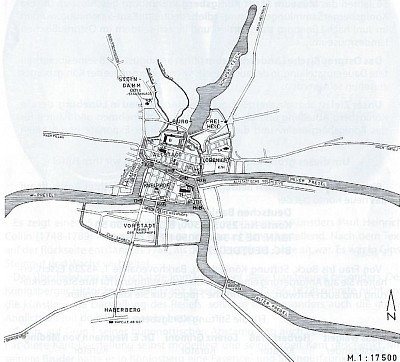

1255: The Teutonic Order destroys the Prussian fort Twangste and begins construction of the Konigsberg fortress, named after King Przemysl Otakar II of Bohemia, who financed the construction. The first settlement to the northwest of the castle, Steindamm, appears.

1262-1263: Konigsberg Castle is besieged during the Prussian uprising, but is liberated by the master of the Livonian Order. Steindamm is being destroyed by the rebels.

1286: In the south, between the castle hill and the Pregoley River, a new settlement appears – Altstadt, which received city rights (Kulm rights).

1300: To the east of Altstadt, between Pregoley and Schlossteich, Loebenicht arises, which also received city rights.

1324-1330: Peter of Dusburg supposedly writes his Chronicon terrae Prussiae (Chronicle of the Land of Prussia) in Konigsberg.

1327: On the island of Kneiphof, in Pregola, south of Altstadt, the third city of Konigsberg is formed, which received city rights.

1340: Konigsberg joins the Hanseatic League, becoming an important trading port for the southeastern Baltic States.

1348: After defeating the Lithuanians in the Battle of Streva, Grand Master Winrich von Kniprode founded a Cistercian convent in Konigsberg. Ambitious students were educated in Konigsberg, and then pursued higher education in other places such as Prague or Leipzig.

1410 (Battle of Grunwald): The Teutonic Order suffers a crushing defeat, but Konigsberg remains under its control. The Livonian Order replaces the Prussian garrison in Konigsberg, helping to rebuild the city occupied by the troops of Vladislav II Jagiello.

Sovereignty of Poland (since 1454)

1440: Konigsberg becomes one of the founders of the Prussian Confederation, which opposes the Teutonic Order.

1454: The Confederation revolts, appealing to the Polish King Casimir IV Jagiellon with a request for the incorporation of Prussia into Poland. Casimir IV agrees, and Prussia (including Konigsberg, named Krulevec) becomes part of Poland. The Thirteen Years' War (1454-1466) begins between the state of the Teutonic Order and the Kingdom of Poland.

1455: Altstadt and Lebenicht side with the Teutonic Order, defeating Kneiphof.

1457: Grand Master Ludwig von Ehrlichshausen takes refuge in Konigsberg. He fled from the Crusader capital to Marienburg Castle (Malbork).

1465: Polish troops destroy the shipyard near Altstadt, preventing the restoration of the Teutonic fleet.

1466: The Second Peace of Thorn ends the Thirteen Years' War. The Teutonic Order remains as a vassal of Poland, and Konigsberg becomes its new capital.

1519-1521: Konigsberg is unsuccessfully besieged by Polish troops led by the great Crown Hetman Mikolai Firlei, but the city advocates peace with Poland.

Prussian Homage: Albert of Brandenburg and his brothers pay homage for the Duchy of Prussia to King Sigismund I the Old of Poland, 1525 (painting by Jan Matejko, 1882).

The Duchy of Prussia

1525: Grand Master Albrecht Hohenzollern liquidated the Teutonic Order as a religious organization, converted to Lutheranism. After paying feudal tribute to his uncle, King Sigismund I of Poland, Albert became the first duke of the new Duchy of Prussia, a Polish fiefdom. After the suppression of the peasant uprising, several leaders were executed.

1544: The University of Konigsberg (Albertina) was founded, with symbolic royal approval from King Sigismund II Augustus in 1560, and became a center for Protestant education.

1561: The first Scot receives the citizenship of Konigsberg.

1566: The rights of the city were expanded, limiting the interference of the dukes in internal affairs, and the Prussian dukes were not allowed to interfere in the internal affairs of the city by the Polish royal commissioners.

1618: After Albert Frederick's death, Prussia passes to the Electors of Brandenburg, beginning the unification of Brandenburg and Prussia.

1635-1636: Polish King Wladyslaw IV Vasa visits Konigsberg, granting the city the right to defend itself against the Swedes and appointing Jerzy Ossolinski as governor.

Brandenburg-Prussia

1618-1648 (Thirty Years' War): The Hohenzollern Court flees to Konigsberg due to the capture of Brandenburg by enemy armies.

1641: Elector Frederick William introduces excise tax in Prussia.

January 1656: Konigsberg Peace Treaty: Prussia is recognized as a feudal possession of Sweden.

1657: Treaty of Warsaw: Frederick William negotiates the liberation of Prussia from Polish control in exchange for an alliance with Poland.

1660: The Peace of Oliva: confirms the independence of Prussia from Poland and Sweden.

1661: Frederick William declares his absolute authority over Prussia (jus supremi et absoluti domini), limiting the powers of the Landtag.

1662: The Konigsberg burghers, led by Hieronymus Roth, resist the absolutism of Frederick William, seeking help from the Polish king. Friedrich Wilhelm suppresses the resistance, and Roth is imprisoned in Peitz.

October 18, 1663: The Prussian estates swear allegiance to Friedrich Wilhelm, but deny him military funding.

1672: Execution of Christian Ludwig von Kalkstein, who tried to enlist Polish support against the Elector.

1673-1674: Frederick William imposes taxes without the consent of the estates and places a garrison in Konigsberg. This leads to a weakening of the political and economic role of the city and an increase in the influence of the Junker nobility.

1668: Frederick William imposes on Konigsberg the acceptance of Calvinist citizens and property owners, despite Lutheran resistance.

Kingdom of Prussia: January 18, 1701

January 18, 1701: Frederick III, Elector of Brandenburg, is crowned as Frederick I, King of Prussia, at Konigsberg Castle. This event marks the elevation of Prussia's status and independence from Poland and the Holy Roman Empire. The former Ducal Prussia becomes the province of Prussia, but Konigsberg remains the capital, although the main residences of the kings are in Berlin and Potsdam.

1709-1710: Konigsberg suffers greatly from the plague epidemic, losing about a quarter of its population.

June 13, 1724: Altstadt, Kneiphof and Lebenicht officially merge into one city of Konigsberg.

1734-1736: During the War of the Polish Succession, Konigsberg became the temporary residence of Polish King Stanislaw Leszczynski and the center of his political activities. After the defeat, Leszczynski signs the act of abdication of the Polish crown in Konigsberg.

Russia in the region (1757-1762)

1756-1763 (Seven Years' War): Russia annexed Konigsberg in January 1758. The Prussian estates swear allegiance to Russia. The city's economy is experiencing growth for a while due to the supply of weapons to the Russian army and trade with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

May 5, 1762: The St. Petersburg Peace Treaty returns Konigsberg to Prussian control.

Kingdom of Prussia after 1773

1773: After the first partition of Poland, Konigsberg becomes the capital of East Prussia. By 1800, the city was growing significantly, reaching 60,000 inhabitants (including 7,000 military personnel).

1806 (Autumn): After the defeat of Prussia in the war of the Fourth Coalition and the occupation of Berlin, King Frederick William III flees to Konigsberg. Konigsberg becomes the temporary capital and center of the Prussian resistance to the Napoleonic occupation.

1807 (beginning): The beginning of the formation of the resistance movement in Konigsberg. The emergence of the beginnings of ideas that would later be embodied in the League of Virtue.

1808 (spring-summer): Founding of the League of Virtue in Konigsberg to promote liberal and nationalist ideas. Work begins on the Städteordnung (new order for urban communities) under the leadership of officials such as Johann Gottfried Frey. This document emphasizes the self-government of the Prussian cities.

1808 (end): Formation of the East Prussian Landwehr (militia) in Konigsberg after the conclusion of the Tauroggen Convention.

1809 (December): French authorities force the dissolution of the League of Virtue. The league's ideas continue to evolve in the Turnbewegung (gymnastic movement) under the direction of Friedrich Ludwig Jahn in Berlin.

1819: The population of Konigsberg is 63,800 people.

1824-1878: Konigsberg was the capital of the united province of Prussia.

1848: Konigsberg becomes the center of liberal resistance to the conservative government. There are 21 episodes of popular unrest in the city during the revolution of 1848. Large demonstrations were suppressed.

1871: Konigsberg became part of the German Empire. By 1888, the construction of a system of fortifications around the city was completed.

Late 19th — early 20th century: The railway and transport infrastructure of Konigsberg is developing. A canal is being built to Pillau, which increases trade. The city's population grew rapidly, reaching 246,000 by 1914. Konigsberg is becoming an important trading center, especially for the export of herring.

The Weimar Republic (1918-1933)

After the defeat of Germany in World War I and the formation of the Democratic Weimar Republic. The Kingdom of Prussia ceased to exist with the abdication of the monarch of the Hohenzollern dynasty William II, and the kingdom was succeeded by the Free State of Prussia. Konigsberg and East Prussia were geographically isolated due to the creation of the Polish Corridor. Despite this, the Government of the Weimar Republic invested in the development of Konigsberg's infrastructure in an effort to support the region's economy:

1919: Construction of Devenau airport, the first civilian airport in Germany.

1920: The opening of the Deutsche Ostmesse (German Oriental Trade Fair), which included the construction of new hotels and radio stations in an attempt to stimulate economic activity.

1929: Modernization of the Konigsberg railway system, including the construction of a new central railway station.

1930: The opening of the North Station in Konigsberg.

The Third Reich (1933-1945)

In 1939, with the outbreak of World War II, the German authorities arrested Polish Consul General Jerzy Warhalowski and other employees of the consulate in Konigsberg, violating international law. Polish students and civilians were harassed and executed. Despite this, the Polish resistance operated in the city, organizing the smuggling of the underground press.

By 1944, there were tens of thousands of forced laborers in Konigsberg, mostly Poles and Soviet citizens, who worked in terrible conditions, deprived of basic rights and subjected to ill-treatment. In the same year, the city was heavily bombed, and the historical center was severely damaged.

In early 1945, Konigsberg was besieged by the Red Army. Many fled before the offensive, especially after rumors of Soviet atrocities. The German garrison, despite declaring Konigsberg an "invincible fortress," surrendered after a three-month siege on April 9, 1945. Before the surrender, the Nazis organized a "death march" for thousands of Jews from nearby camps. As a result of the fighting, about 42,000 people died (according to German estimates), and the Red Army captured more than 90,000 people.

In Koenigsberg in the 1930s, the Nazis quickly consolidated power by using violence against political opponents. In 1932, the SA carried out terrorist attacks, culminating in the assassination of Communist Gustav Zauf and an attack on the headquarters of the Social Democrats. After Hitler came to power, "Aryanization" began: Jewish shops were confiscated, books were burned, monuments of Jewish origin were removed, Jews were dismissed from the university. In July 1934, Hitler spoke in Konigsberg in front of 25,000 supporters. The NSDAP won 54% of the vote in the 1933 city elections. The opposition was persecuted, newspapers were banned, and the House of Social Democrats turned into the headquarters of the SA, which was used for torture. Many were sent to concentration camps. By 1935, Konigsberg had become the headquarters of Military District I. The population of the city in 1939 was 372,164 people. Konigsberg played a key role in the German communications network during World War II, and his teletypes and cipher machines were the target of British intelligence. The Jewish population of Konigsberg, which numbered 3,200 in 1933, declined sharply due to persecution and deportations to concentration camps that began after the Wannsee Conference in 1942. The synagogue was destroyed during Kristallnacht. There were also forced labor camps for Jews and Gypsies in the city. Poles were also persecuted.

After World War II, Konigsberg, which became Kaliningrad, experienced massive destruction and deportations of the German population. The underground bunker of Lasha, preserved to this day as a museum, serves as a reminder of those times.

According to various sources, the picture of demographic changes is as follows:

Survivors of the war: About 120,000 German civilians remained in the destroyed city. Lithuanians, who made up a small part of the pre-war population, received a residence permit.

Forced labor: The German population was subjected to forced labor until 1946.

Mass deportation (1947-1950): Between 1947 and 1950, the German population was forcibly resettled: about 100,000 people were deported in 1947-1948, and the remaining 20,000 in 1949-1950. Soviet documents indicate the deportation of 102,407 people from the region as a whole (from April 1947 to May 1951), but the exact number of those deported from Konigsberg is unknown.

Conflicting population figures: Soviet sources point to 68,014 Germans in Konigsberg in September 1945, and German historian Andreas Kossert estimates the number of German civilians in the city at 100,000 to 126,000, suggesting that only 24,000 of them survived the 1947 deportation. He also points to the causes of death: hunger (75%), epidemics (2.6%) and violence (15%). A significant discrepancy in the data requires additional research to establish accurate figures.

Soviet Kaliningrad

1945-1946: The transition period and the beginning of transformations

August 1945: Potsdam Conference. The decision to transfer Konigsberg to the USSR is temporary ("until the final resolution of territorial issues in a peaceful settlement"). The wording of the border, which runs along the pre-war border with Lithuania, is ambiguous and still causes debate among historians. Some interpret this as an intention to transfer the territory under the jurisdiction of the Lithuanian SSR.

Autumn 1945 - 1946: The gradual eviction of the German population begins. This process was not instantaneous, but took place in stages, often in terrible conditions and with the use of violence. The exact numbers of those killed and deported are still a matter of debate. In parallel, the settlement of the region by Soviet citizens begins. It was not just a "move", but a purposeful migration policy designed to change the demographic composition of the region. The exportation of the German population and settlement by Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians occurred in waves over several years.

1946: The renaming of Konigsberg to Kaliningrad. Choosing the name of Mikhail Kalinin, who had nothing to do with the city, was most likely a politically motivated decision. The existence of other cities named Kalinin also points to symbolism associated with Soviet ideology. The formal incorporation of the Kaliningrad Region into the RSFSR. Work is beginning to rebuild the destroyed infrastructure, although it has been extremely slow and uneven.

1947-1950: Deportations and consolidation of Soviet power

1947-1948: Peak of deportations of the German population. Tens of thousands of people were forcibly evicted from their homes and sent to other regions of the USSR. Official Soviet statistics do not always correspond to reality, and the number of people killed in the deportation process is still unknown for sure.

1950: Kaliningrad's population reached 1,165,000. This figure is about half of the pre—war population. This demonstrates the scale of demographic changes in the city.

Late 1940s - early 1950s: An active campaign for the Russification of the city and region. The forcible imposition of the Russian language, culture, and ideology. Closure of German schools and institutions.

1950s - 1980s: Construction of a "new" city and isolation from the outside world

1953-1962: Installation of the monument to Stalin on Victory Square. A symbol of Soviet power and the suppression of dissent. It was dismantled after the "exposure of Stalin's cult of personality," but the very fact of its existence for a decade is significant.

1957: Delimitation of the border between Poland and the USSR. Securing the borders of the Kaliningrad region.

1959: Installation of a monument to Kalinin. The demolition of Konigsberg Castle. This event is one of the most controversial moments in Kaliningrad's history.

1970s - 1980s: Kaliningrad continues to develop as an industrial and port city. Construction of new residential areas and infrastructure facilities. However, the "restoration" of the city was not aimed at preserving the historical heritage, but rather at creating a new, Soviet city. Kaliningrad remains almost completely closed to foreigners.

⦁ Development of oceanic fisheries: The post-war "reconstruction" of the region, including solving the problem of hunger, was partly due to the development of fishing, which allowed the creation of an important branch of the economy.

Strategic importance and offer of the Kaliningrad region of Germany:

- Control of the USSR: There is an opinion that the inclusion of the Kaliningrad region into the RSFSR, rather than the Lithuanian SSR, was due to its strategic importance for the USSR. The coastal location, proximity to the borders of other countries, as well as the presence of a port made the region too important to transfer it to the control of another union republic. This explains why, despite the fact that the territory was initially under the jurisdiction of the planning Committee of the Lithuanian SSR, the region eventually became a separate part of the RSFSR.

- Lithuania's refusal: Nikita Khrushchev's proposal in the 1950s to transfer the Kaliningrad Region to the Lithuanian SSR was rejected by the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Lithuania, Antanas Snechkus. The reason for the refusal is the potential increase in the Russian population in Lithuania by one million people. This indicates the difficulty of integrating the region into the existing structures of the Lithuanian SSR and political considerations.

- German proposal (1990): In 2010, Der Spiegel published an article about an alleged proposal to transfer the Kaliningrad Region to Germany in 1990 for a fee. This information, however, was refuted by Mikhail Gorbachev. This episode illustrates the complexities of political negotiations during the period of perestroika and the unification of Germany, and also shows that the question of belonging to the Kaliningrad region remained a subject of discussion even after the collapse of the USSR. The possibility of returning German territory was not seriously considered by the West German government, whose priority was reunification with the GDR.

The time line presented earlier can be supplemented by the following points:

1945-1950s: Despite the formal leadership of the Planning Committee of the Lithuanian SSR, the Kaliningrad Region remains under strict Soviet control due to its strategic importance. Moscow's influence is strengthening. In parallel, the gradual and forced eviction of the German population, as well as the settlement of the territory by Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians, is being carried out. Geographical features are being renamed to Russian.

1950s: Khrushchev's proposal to transfer the region to the Lithuanian SSR is rejected due to Antanas Snechkus' concerns about demographic imbalance.

1990: Information appears (refuted by Gorbachev) about a proposal to transfer the Kaliningrad region to Germany. This episode highlights the complexity and ambiguity of the region's post-war status and its long-term importance in a geopolitical context.

Kaliningtad now

1991-2000: Perestroika, isolation and the first steps

1991: The collapse of the USSR. Kaliningrad region becomes an exclave of Russia, completely separated from the rest of the country by independent states — Lithuania and Poland. This creates serious problems in the transport logistics and economy of the region. A period of uncertainty and adaptation to the new geopolitical situation is beginning.

Mid-1990s: The first attempts at economic development appear. The Yantar Free Economic Zone is being created, designed to stimulate investment and attract foreign capital. Economic reforms lead to social instability, rising unemployment and falling living standards.

2000-2010: Integration and geopolitical tensions

2000s: Improvement of the economic situation, growth of investments and development of infrastructure. The region is increasingly integrating into the Russian economic system. However, problems of corruption and inequality persist.

2004: Poland and Lithuania join NATO and the European Union. This increases the political isolation of the Kaliningrad Region, since all land communications with the rest of Russia pass through the territories of NATO and EU member states. Special conditions for the movement of residents of the Territory were organized through a Lightweight Transit Document (FTD) and a Lightweight Railway Transit Document (FRTD).

2005: Kaliningrad celebrates its 750th anniversary.

2007-2009: Tension in relations with the West over plans to deploy U.S. missile defense systems in Poland. Russia has announced the possibility of deploying nuclear weapons in the Kaliningrad region, but these plans are later suspended.

In 2009, the head of the city administration, Felix Lapin, stated that he personally supported the return of the historical name to the city.

2011: Commissioning of the Voronezh long-range radar at Pionerskoye (formerly German Neukuhren), capable of tracking missile launches over considerable distances. This demonstrates the increasing military importance of the region. The governor of the Kaliningrad Region, Nikolai Tsukanov, proposed holding a referendum to resolve this issue, but said he opposed the renaming. Since then, no further plans have been announced.

2010-2025: Geopolitical tensions, sanctions and isolation

2010s: The rise of geopolitical tensions related to the events in Ukraine. Deterioration of relations with the EU and the Baltic states. The imposition of sanctions against Russia.

2018: Kaliningrad becomes one of the host cities of the FIFA World Cup. This event drew attention to the region, but did not solve the main economic and political problems.

2020s: The COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating economic problems. Increasing isolation from the international community.

2022: The government officially confirmed that renaming the city would be "impractical."

February 2025: Kaliningrad's power grid is disconnected from Russia's power grid due to the interruption of the interconnector in Vilyak by the Baltic States. An estimated $1 billion had to be spent (partly on additional gas-fired power plants) to balance the domestic grid.

Geography

Kaliningrad Region: a brief geographical and economic overview

1. The name of the region and the composition of the territory:

Kaliningrad Oblast is a subject of the Russian Federation, an exclave separated from the rest of Russia by the territory of Lithuania and Poland. It includes the territory of the former East Prussia.

2. Economic-geographical and political-geographical location. The impact of EGP on development:

The region is located on the Baltic Sea coast, bordering Lithuania and Poland. Such an exclave position defines both advantages (proximity to the EU, access to sea routes) and serious difficulties (dependence on transit traffic, limited access to Russian markets). The economic development of the Kaliningrad Region significantly depends on successful cooperation with neighboring countries and solving problems related to the transit of goods and people.

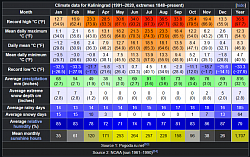

3. Climate:

Temperate marine climate with mild winters and cool summers. Precipitation is distributed evenly throughout the year. The climate is favorable for agricultural development, but it is affected by western cyclones.

4. Natural resources and their use. Assessment of natural resource potential for industrial and agricultural development:

The subsoil is rich in amber (the world's largest deposit), peat, and building materials. The soils are relatively fertile, especially in the southern regions. Forest resources are moderate. The natural resource potential is limited, which hinders the development of resource-intensive industries. Agriculture develops mainly on the basis of resource imports.

5. General characteristics of the farm. Reasons affecting the pace of economic development:

The region's economy is diversified, but with a predominance of manufacturing, transport, and tourism. The pace of economic development is constrained by the exclave position, lack of investment, dependence on foreign trade relations and fluctuations in world markets.

6. Geography of the main industrial complexes and industries:

The food industry (fish processing, dairy industry), mechanical engineering (mainly repair facilities), and light industry are developed. The main industrial centers are Kaliningrad, Sovetsk, and Baltiysk.

7. Specialization of agricultural production:

Dairy farming, the cultivation of cereals, potatoes and vegetables prevail. Fishing and fish farming are well developed. The lack of own resources (feed, fertilizers) limits the development of the agricultural sector.

8. Development of the transport complex:

Sea, road and rail transport are important. Seaports (Kaliningrad, Baltiysk) play a key role in foreign economic relations. Transit traffic through Lithuania and Poland is a critical issue for the development of the region.

9. Socio-economic development of districts within the region. The reasons for the uneven socio–economic development of individual areas:

The most developed areas are located near Kaliningrad and seaports. The hinterlands are lagging behind in socio-economic development due to lack of investment, limited employment opportunities, and weak infrastructure. The uneven development is also due to historical factors and the uneven distribution of resources.

10. External economic relations:

Kaliningrad Region actively cooperates with EU countries, mainly in the field of transit, trade and tourism. Foreign economic activity plays a crucial role in the region's economy. However, sanctions restrictions and political factors have a negative impact on these ties.